Last Updated on September 6, 2022 8:35 am

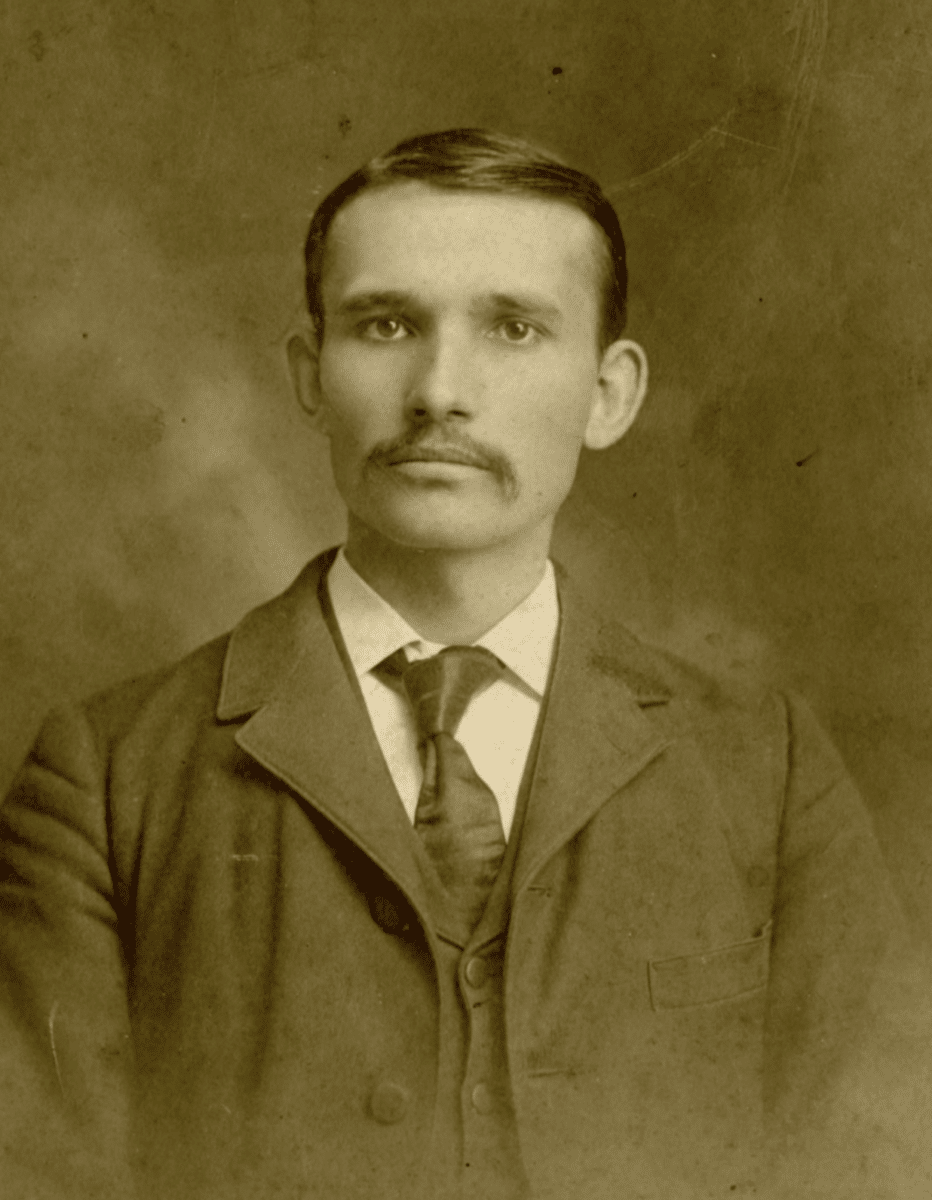

As part of ongoing activities associated with the Boone 150 celebrations in 2022, marking the 150th anniversary of Boone’s official incorporation as a town on January 23, 1872, the Watauga County Historical Society (WCHS) has established the Watauga County Historical Society Hall of Fame. Throughout 2022, WCHS will name twelve individuals or groups—one each month—as members of the inaugural class of the WCHS Hall of Fame. For the month of August 2022, the WCHS announces that Blanford “Blan” Barnard Dougherty (1870-1957) has been named as the next inductee of this inaugural class of the WCHS Hall of Fame.

Blanford Barnard Dougherty was born to Daniel Baker Dougherty (1833-1902) and Ellen Carolina Bartlett Dougherty (1845-1876) on October 21, 1870, at Boone. In his youth, he lived in a home on the south side of King Street that had once been Jordan Councill, Jr.’s store and post office, and which was later incorporated into the Greene Inn. His education at Boone was in a one-room, log schoolhouse near Boone Creek, then at the Boone Academy, a two-room building later briefly used in the early days of Appalachian State University’s history as the Watauga Academy. His high school training was limited to less than a year, involving training at the New River Academy, located well east of Boone, as well as Lenoir High School and the Globe Academy. By 1888, Dougherty managed to pass the required teacher certification exams, then became a teacher at community schools in Shulls Mill and Blowing Rock, despite his lack of any significant, formal education. Other posts quickly followed at the Zionville School, the Globe Academy, and the Hamilton Institute. After abbreviated college education forays at Wake Forest College and Holly Spring College, Dougherty returned to the Globe Academy and served as its principal for two years.

Dougherty then enrolled at Carson-Newman College in Tennessee, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1896. He taught briefly at Holly Spring College before enrolling at UNC-Chapel Hill, where he earned a degree in pedagogy in 1899. That fall, Dougherty and his brother, Dauphin Disco Dougherty (1869-1929), established the Watauga Academy at Boone, funding the teacher training institute primarily through private subscription and their own resources. In early 1903, seeking to secure state support for the academy, Dougherty approached local attorney E. F. Lovill about drafting a bill for this support. Narrowly passed in March 1903, the Newland Bill established the Appalachian Training School and provided significant state funding for its high school operations. Name changes followed in 1925 (Appalachian State Normal School), when the school became a two-year, degree-granting college that offered demonstration schools run jointly with Watauga County, and again in 1929 (Appalachian State Teachers College, or ASTC), when the school began offering bachelor’s degrees. Dougherty, who had served as co-principal and then superintendent to that point, was named president of the school in 1925.

Meanwhile, Dougherty also served as the superintendent of county schools (1899-1916), leading a major building campaign in the early twentieth century that dramatically improved county schools. He was later awarded two honorary doctoral degrees for his accomplishments in education. For much of the early twentieth century, Dougherty was also keenly attuned to the county-to-county educational funding inequities that prevailed during the early twentieth century, whereby the children of wealthier counties enjoyed better educational opportunities than children living in poorer, more rural counties like Watauga. Dougherty advocated for more than twenty years for a tax and education equalization scheme, politicking with legislators and major business leaders, the latter of whom were most directly impacted by and thus resistant to the scheme, to embrace what became known as the Hancock Bill (despite Dougherty’s authorship of the bill). This legislation was intended to equalize (white) educational opportunity throughout the state by forcing wealthier, more populous counties to pay higher taxes to help fund the educational needs in poorer counties. Passage of the bill in 1929 finally resulted in a standardized nine-month school term (the old term in Watauga had been four months) and highly trained teachers who were dispersed throughout the state.

Dougherty occasionally proved to be forward thinking on Black education late in his career, once appointing a committee of ASTC educators in 1941 to work with committees from Asheville College and Western Carolina Teachers College on “studying and discussing methods of improving the educational conditions of the negro race in the mountains of North Carolina.” He also reportedly advocated during the 1950s for equal pay for all teachers regardless of race, despite the state’s slow action on this front. Unfortunately, Dougherty’s legacy on racial matters is tarnished by several events covered in the local press during his lifetime. First, as a young teacher at the Globe Academy in May 1891, Dougherty took part in a debate that was part of the school’s closing exercises program. At issue was a resolution affirming “that the introduction of the negro into America has been productive of more good than evil.” Dougherty was one of three orators that the Watauga Democrat said “seemed to take a delight in representing the negative,” which reportedly carried the day. While such views might easily be explained as the indiscretions of a young man who had been raised by a Confederate veteran, expressed at the height of the Jim Crow era’s influence on racial views in the South, such considerations do not explain Dougherty’s well-documented penchant—late into his adult years as president of ASTC—for regaling the ASTC faculty and their families with “negro stories” at social events. When confronted in 1935 over how he obtained funding for ASTC’s power plant without a state appropriation being made for that purpose, Dougherty replied with a “negro story” that included dialect as part of the punchline. Indeed, the two “special hobbies” attributed to him following his death were “soil conservation and improvement” and “talking with Negroes.” Also troubling were reports in 1933 that Dougherty was “especially provoked…that the State was compelling him to maintain his Appalachian college for the training of white teachers on a per capita basis of $40 while it was allowing the Winston-Salem college for the training of negro teachers a per capita cost of $119.”

Outside of their educational work, the Dougherty brothers used their operations at the Appalachian Normal School to improve living conditions for many of the residents of Boone. In 1915, they established the New River Light and Power Company, whose electrical service was originally intended to serve only the school but was almost immediately extended to some local residents. Blan Dougherty also served as the county campaign chairman for the War Savings Stamps Campaign during World War I. More significantly, Dougherty was a fierce advocate for bringing a railroad to Boone, and in 1917 and 1918, he played a direct role in securing rights of way from property owners between Shulls Mill and Boone for the extension of the Linville River Railway to Boone. After World War I, Dougherty also lobbied strenuously for the Good Roads campaign designed to bring improved automobile access to the “Lost Provinces” of northwestern North Carolina. His direct action with local citizens led to the paving of the Boone Trail Highway from Yadkinville to Boone in 1931. In later years, his efforts also helped secure the extension of US 321 into Tennessee in 1957. Dougherty also played a key role in the “Watch Boone Grow” campaign of the 1920s, which took advantage of the arrival of the railroad and its ability to import heavy freight to completely transform both Boone’s downtown and the ASTC campus. In 1931, Dougherty also partnered with Dr. H. B. Perry using WPA funds to construct a new Watauga County Hospital on the ASTC campus (today known as Founders Hall), which served the community for nearly three decades.

Citing ill health, Dougherty retired at age 83 as president of ASTC in 1955. In addition to his long period of service at ASTC, he also served as the president of the Northwestern Bank in Boone from 1947 to 1957, and he served on numerous state commissions, including the State Textbook Commission (1916), the State Board of Equalization (1927-1933), the State School Commissions (1933-1941), and the State Board of Education (1941-1943, 1944-1957). He was also a member of the Boone Baptist Church, and he and his brother’s family provided the land for the present site of the church as well as its former parsonage. He was named to the North Carolina Education Hall of Fame in 1962.

The WCHS Hall of Fame honors individuals, either living or dead, who have made significant and lasting contributions to Watauga County's history and/or literature, including those whose efforts have been essential to the preservation of Watauga County's history and/or literature. Honorees need not have been residents of Watauga County. The WCHS is particularly interested in honoring individuals who meet the above criteria but who may have been overlooked in traditional accounts of Watauga County's history and literature, including women and people of color. Selections for this inaugural class were made from nominations submitted by members of the Digital Watauga Project Committee (DWPC) of the WCHS. Beginning in 2023, the WCHS will also consider nominations from members of the public, which in turn will be evaluated by the DWPC.