Last Updated on January 3, 2024 5:11 pm

The Watauga County Historical Society (WCHS) is delighted to announce that Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson (1923-2012) is the third of three inductees to the 2023 class of the WCHS Hall of Fame. Born on March 3, 1923, in Deep Gap, North Carolina, Doc Watson was the sixth of nine children born to General Dixon Watson and Annie Greene Watson. Before the end of his first year, Arthel began losing his eyesight due to an infection complicated by a vascular disorder. Doc’s father gave him a harmonica at a very young age, and by the time he was five, Doc was picking the banjo. His parents later sent him to the North Carolina State School for the Blind and Deaf (now the Governor Morehead School) in Raleigh, where he learned his first guitar chords. His first banjo was a fretless one made for him by his father when Doc was 11. Shortly thereafter, Doc purchased his first guitar with money he earned from chopping down dead chestnut trees on his father’s property and selling them to a local tannery as fuel.

Watson frequently claimed that he had never had a formal music lesson, relying instead on listening to the songs that family members sang and that he heard on the radio. In a 1969 interview, Watson revealed that he learned many of his covers of traditional folk songs by listening repeatedly to Eugene “Gene” Earle’s old 78-speed recordings of country and western, blues, and jazz performances. Other strong influences included the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers. His earliest formal performances were probably walk-on gigs at fiddlers conventions. Watson often told the story that he earned his nickname at the age of 19, when the emcee at a radio gig in a Lenoir furniture store asked him what stage name he wanted to use, prompting a girl in the crowd to suggest, perhaps in reference to Sherlock Holmes’s sidekick, “Call him ‘Doc’!”

By the time he was 20, Doc was a fixture in downtown Boone, often busking on King Street and Depot Street, sometimes with his brother Linny. Locals immediately took notice. As part of Kermit Dacus’s bootleg radio shows out of the Appalachian Theatre in 1943, Doc appeared on stage on September 11 and 18 as part of a “Hillbilly Jamboree,” billed with his nickname as “the Blind Boy with the Million Dollar Voice.” In 1945, he appeared as “Dock Watson (the Blind Boy) and His Blue Ridge Hillbillies” in a concert at the Watauga County Courthouse and was billed as “Dock Watson, the man with the flying fingers” for a gig at Elkland High School in Todd the next year. From there, Doc appeared with other local groups and fronted another act, Doc Watson and the Watauga Wildcats, for a square dance at Boone High School in 1950. Meanwhile, Watson married his Deep Gap neighbor Rosa Lee Carlton before a Boone Justice of the Peace in 1946. The marriage produced two children, Eddy Merle (1949) and Nancy Ellen (1951). To earn a living in those early years, Watson tuned pianos and continued to busk on Boone’s streets.

Watson was featured in radio shows and television broadcasts as early as 1953, when he was touring with Charles Osborne and Frog Greene, and sometimes performing on electric guitar with Jack Williams’s country and western swing band in Johnson City. According to a 1969 interview with Watson, his first truly big break occurred in 1960, when Ralph Rinzler (1934-1994), an important folk musician in his own right, came to a Union Grove fiddlers convention looking for “oldtime musicians” and heard Doc playing in a pick-up band with noted folk musician Clarence “Tom” Ashley (1895-1967), prompting Rinzler to form a new group called “Clarence Ashley and His Friends” that included Watson. Shortly thereafter, Rinzler persuaded Doc to give a solo concert in Lafayette, Indiana, which went poorly, but the next night, Doc’s concert in Urbana, Illinois, secured his gig as a recording musician on Vanguard Records between 1961 and 1964, with Rinzler as his manager.

As a master of both fingerpicking and flatpicking, Doc’s smooth, seamlessly clean style gradually persuaded other folk artists that the guitar could be a lead instrument, supplanting the usual mandolin, banjo, or fiddle. By 1964, Watson was playing the folk festival circuit, showcasing his talents on the guitar, five-string banjo, mandolin, and harmonica, his son Merle frequently accompanying him. His performances prompted the New York Times that year to describe him as “one of the most inventive guitar players ever recorded” and “almost the object of a cult among folk music fans.” But it was Doc’s haunting, yearning baritone voice on folk song and blues covers like “Wayfaring Stranger,” “Little Sadie,” “The Cuckoo,” “Deep River Blues,” “Shady Grove,” and “Omie Wise” that tied together so many of his performances and kept audiences rapt. “Few singers out of the southern Appalachians,” the New York Times added in 1964, “are so able to evoke another time, another place, another set of standards.”

From the folk revival of the 1960s forward, Doc was an internationally recognized and highly respected performer. He frequently teamed with other folk and bluegrass artists on the circuit and in the recording studio, including Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, Jimmy Martin, Vassar Clements, and Merle Travis. But Doc’s fame and immense popularity did not dissuade him from returning home, where he continued to give local performances, such as his 1965 concert at Appalachian State Teachers College and his headlining of the Bluegrass and Folk Jamboree sponsored by the Boone Jaycees at Watauga High School in 1968, where locals were comically urged to “be there early in order to get a good seat.” It was Doc’s pairing with his son Merle, however, that earned them continued fame in the 1970s and early 1980s, producing thirteen albums as a duo along with two Grammy Awards in 1974 and 1979. Merle’s death in a tractor accident in Caldwell County in 1985 was a devastating blow, prompting Doc to create the MerleFest music festival in Merle’s memory in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, in 1988, which Doc hosted until his death. Watson continued to perform and tour in his later years, often with his grandson Richard Watson or with longtime collaborators David Holt and Jack Lawrence.

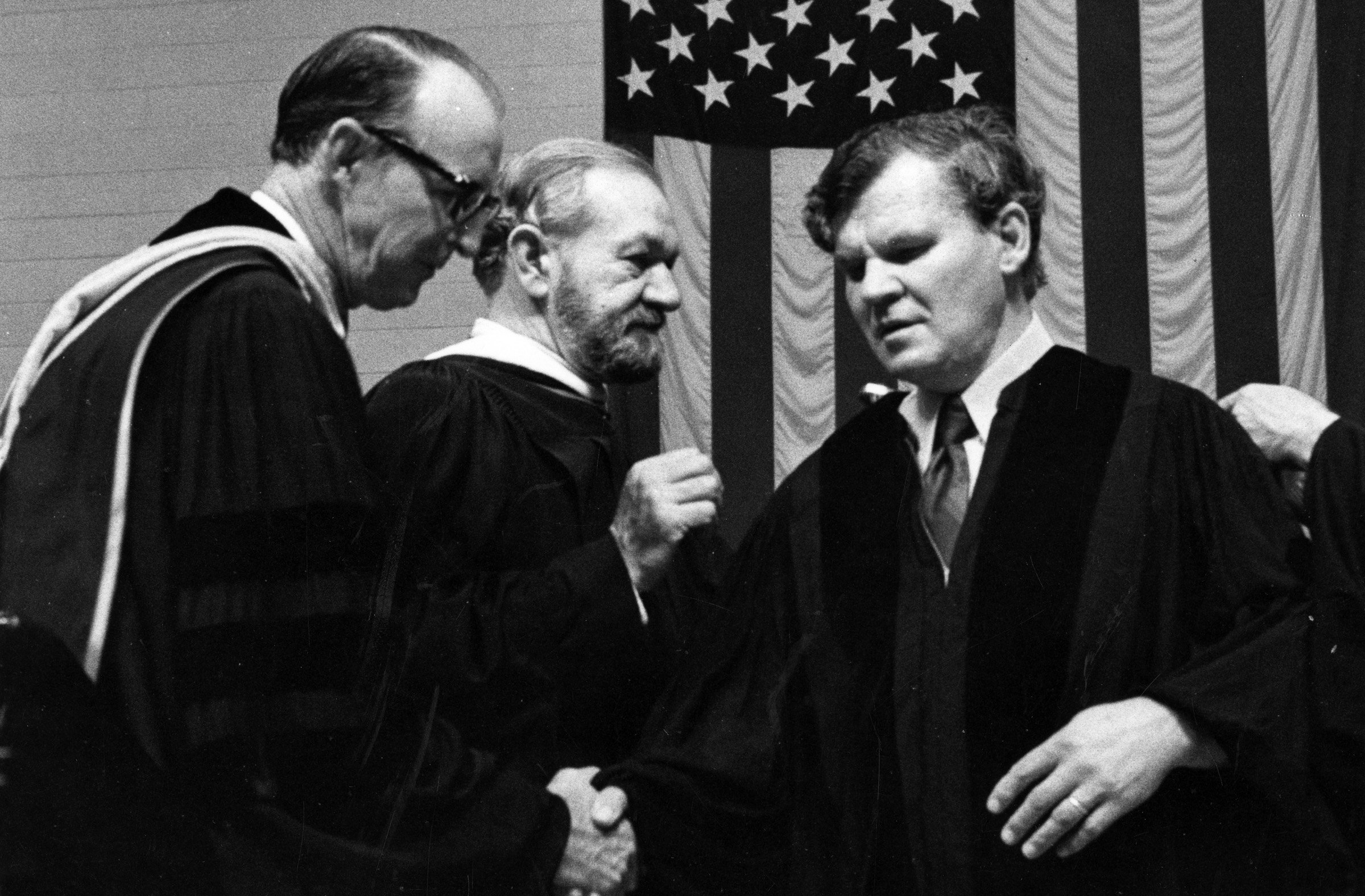

In all, Doc Watson recorded nearly 30 albums and more than two dozen collaborations and compilations, and he earned seven Grammy Awards for his performances, as well as a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award in 2004. Other career honors included the 1986 North Carolina Award in Fine Arts, the highest civilian award given by the state; a 1988 National Heritage Fellowship; the 1994 North Carolina Folk Heritage Award; and the 1997 National Medal of Arts. He received at least two honorary academic degrees from Berklee College of Music and Appalachian State University. Watson was inducted into the International Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame in 2000 and the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame in 2010. On June 24, 2011, the Town of Boone unveiled a life-sized bronze statue of Watson at the northeast corner of King and Depot Streets as part of the first Doc Watson Day celebration. Watson was also an important presence at the first meetings of the Appalachian Theatre Task Force in 2011, inspiring many of those present to work tirelessly together for the preservation and renovation of the Appalachian Theatre, which reopened in 2019. Watson died in May 2012 following surgical complications.

The WCHS Hall of Fame honors individuals, either living or dead, who have made significant and lasting contributions to Watauga County’s history and/or literature, including those whose efforts have been essential to the preservation of Watauga County’s history and/or literature. Honorees need not have been residents of Watauga County. The WCHS is particularly interested in honoring individuals who meet the above criteria but who may have been overlooked in traditional accounts of Watauga County’s history and literature, including women and people of color. Selections for this class were made from nominations submitted by members of the Digital Watauga Project Committee (DWPC) of WCHS as well as the public.