Last Updated on August 11, 2015 12:53 pm

Fisheries biologists with the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission are again asking for anglers’ assistance after reports of gill lice on rainbow trout in three western North Carolina trout streams were confirmed last week.

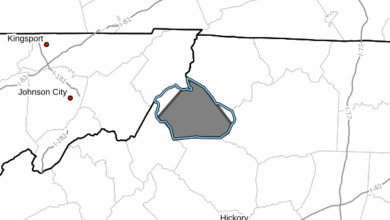

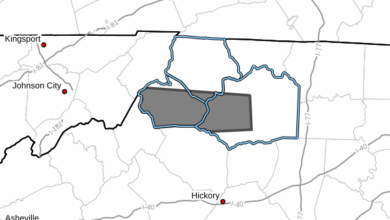

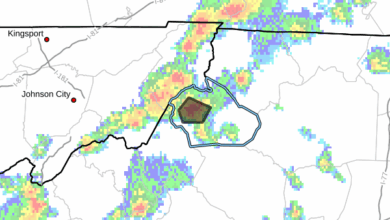

These new reports of gill lice came on the heels of the recent confirmation of whirling disease in rainbow trout collected from the Watauga River. This is the second time that gill lice have been found in trout in North Carolina waters. Gill lice were first discovered on brook trout on the Cullasaja River watershed in Macon County in 2014. The gill lice confirmed last week were found on rainbow trout collected from the West Fork Pigeon River in Haywood County and Boone Fork Creek and the Watauga River in Watauga County.

Biologists ask that anglers fishing for trout in any waters in western North Carolina be especially diligent when cleaning their fishing equipment and offer these recommendations:

- Remove any visible mud, plants, fish or animals before transporting equipment;

- Eliminate water from equipment before transporting; and,

- Clean and dry anything that comes into contact with water.

The Commission has a dedicated Angler Gear Care webpage that lists other steps anglers can take to help prevent the spread of aquatic nuisance species.

In addition, biologists stress the importance of not moving fish from one body of water to another. Not only is it illegal, but it is also one of the primary ways gill lice, whirling disease and other aquatic nuisance species are spread.

“Illegal stockings can have unforeseen and irreversible consequences,” said Doug Besler, the Commission’s fisheries supervisor for the Mountain Region. “The fact that we now have four confirmed cases of gill lice established in wild trout populations within the last year shows how rapidly nuisance species can spread.”

Gill lice—tiny, white crustaceans also known as copepods—attach to a fish’s gill, which can damage gills and inhibit the fish’s ability to breathe. While most fish are able to tolerate a moderate infestation of gill lice, some fish, particularly those that are suffering from other stressors like drought or high water temperatures, can succumb to a gill lice infestation. Impacts to local trout populations can be devastating.

The gill lice reported last week on rainbow trout in the West Fork Pigeon River, Boone Fork Creek and Watauga River is a different species of gill lice than the one found on brook trout in 2014. That one, Salmincola edwardsii, is found only on brook trout, while this latest species, Salmincola californiensis, is known to infect not only rainbow trout but also kokanee salmon. The only population of kokanee salmon found in North Carolina is in Nantahala Lake in Clay and Macon counties.

The confirmation of this new species of gill lice is particularly concerning to fisheries biologists because it highlights the ongoing and increasing threat that aquatic nuisance species pose to native aquatic wildlife, and how quickly and easily they can spread.

Aquatic nuisance species — either plants or animals — are organisms that cause ecological and/or economic harm when moved outside their historical range. In the mountain region, whirling disease and gill lice are aquatic nuisance species most troubling to biologists right now because of their impacts on trout populations.

“While whirling disease can be fatal for infected individuals, gill lice may not directly lead to substantial mortalities in trout populations; however, their presence is a stressor that is cumulative over time,” Besler said. “Each new stressor, whether it’s drought, or high water temperatures, or even another aquatic nuisance species, is additive in terms of stress placed on each infected trout and those stresses can add up to declines in abundance if enough individuals are affected.”

However, in other parts of the state, one of the most troublesome aquatic nuisance species isn’t an animal or a parasite but rather a plant that spreads rapidly and forms dense mats that can take over a good fishing spot, consume oxygen and cause fish kills. Hydrilla, a non-native aquatic plant, is having major impacts in the Eno River in Durham County, Lake Waccamaw in Columbus County and reservoirs throughout the state because of its tendency to spread quickly, outcompeting native vegetation and interfering with boating, swimming, fishing and other water-related activities.

Throughout the Great Lakes Region and in the Mississippi River Basin, quagga mussels and zebra mussels are wreaking havoc on waterways, causing issues with boaters, swimmers and others who enjoy water-related recreation. These species have not been found in North Carolina waters — yet. Biologists continue to work with anglers and boaters to keep these species from being introduced in North Carolina and causing similar problems. Although the vast majority of aquatic nuisance species are non-natives, a few, such as white perch and river herring, are species native to the Atlantic Coast that have become nuisance species after they were introduced into North Carolina reservoirs where they weren’t historically found and began outcompeting, or even preying on, the native fishes found in those reservoirs.

Lake James is an example of a reservoir where white perch and river herring have been introduced. In their native coastal rivers, river herring are an important food fish for other fish species and white perch are popular game fish for anglers. However, in Lake James, they have preyed on walleye eggs and have effectively eliminated walleye reproduction. As a result, the Commission has implemented a walleye fingerling stocking program in Lake James to maintain this popular fishery.

“Anyone, whether you’re an angler or a boater or just someone who enjoys using our waters, can help prevent the spread of aquatic nuisance species,” Besler said. “Once established, they can be nearly impossible to eradicate and can diminish fishing opportunities for decades to come.”

For more information about whirling disease, visit the Commission’ Whirling Disease webpage. For more information about other aquatic nuisance species, visit the Protect Your Waters website.