Last Updated on June 25, 2021 11:46 am

BOONE, N.C. — Spreading avens, a rare plant that thrives in Western North Carolina — at elevations of more than 4,000 feet — is in danger of extinction.

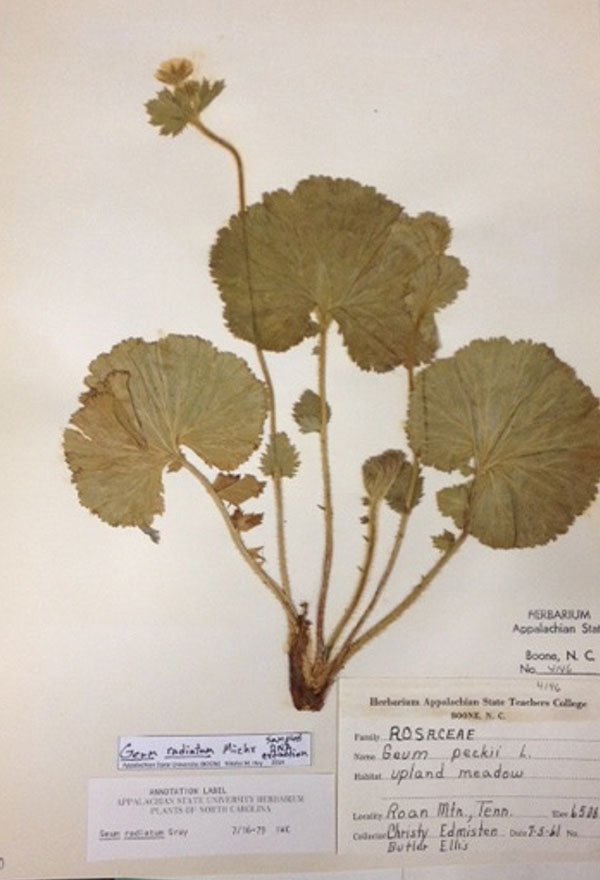

To help preserve and protect this federally endangered plant, whose scientific name is Geum radiatum, Appalachian State University’s Dr. Matt Estep has begun a five-year study to examine the genetic diversity and sustainability of populations located at Roan Mountain. The 2020–25 project is funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Part of the rose family, Geum radiatum is a perennial herb, growing to more than 20 inches and blooming bright yellow flowers from June through September. The plant is native to the Southern Appalachian Mountains and found only on high-elevation mountain peaks in Western North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee.

According to Estep, a plant geneticist and associate professor in App State’s Department of Biology, the plant species is vulnerable to extinction due in part to climate change, land development and outdoor recreation.

Estep and App State biology students will work with Blue Ridge Parkway plant ecologist and arborist Dr. Chris Ulrey, who monitors the species yearly. They will collect leaf tissue samples to be used in the genetic diversity analyses conducted in Estep’s on-campus lab at App State.

The project will provide a greater understanding of the genetic sustainability of spreading avens, Estep said, and help inform conservation strategies for the species, as well as for other long-lived perennials.

A genetic rescue for spreading avens

In the 1990s, a conservation technique known as genetic rescue was applied to help bolster failing subpopulations of spreading avens on Roan Mountain, which spans the North Carolina–Tennessee border. This included bringing in a genetically diverse population of the plant to crossbreed with the mountain’s native population.

Estep said the focus of his study is to better understand the effects of that intervention — specifically, whether it positively or negatively affected the genetics of the plants’ hybrid offspring.

By connecting the study’s genetic data with 20-plus years of demographic data on the plant generated by Ulrey, Estep will be able to evaluate the fitness of those plants native to Roan Mountain, those that were brought in from another location and their hybrid offspring, he said.

In his App State lab, Estep and Morgan Gaglianese-Woody ’19, of Charlotte, a graduate student in the university’s biology-ecology and evolutionary biology program, will determine if the hybrid offspring are stronger, or healthier, than their parents — or less so.

According to Estep, more spreading avens are preserved in herbaria than exist in the wild. App State’s on-campus herbarium, containing approximately 29,000 plant specimens from around the world, includes spreading avens in its collection, which serves as a valuable teaching and research tool for App State students and faculty, Estep said.

Undergraduate biology students at App State will be involved in fieldwork for this project, Estep said, and he will incorporate findings from the study into his undergraduate course on conservation genetics.

Estep said this type of hands-on fieldwork gives students the opportunity to learn more about outdoor careers in biology, as well as performing field observations — experiences that cannot be taught in the classroom, he added.

Fieldwork also allows students to network and interact with state and/or national park professionals — a gateway to available jobs within the land management and conservation disciplines, Estep said.

Estep has served as a thesis adviser to several undergraduate students in the Department of Biology’s honors program and the university’s Honors College.

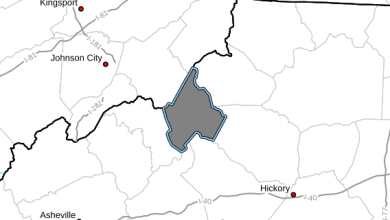

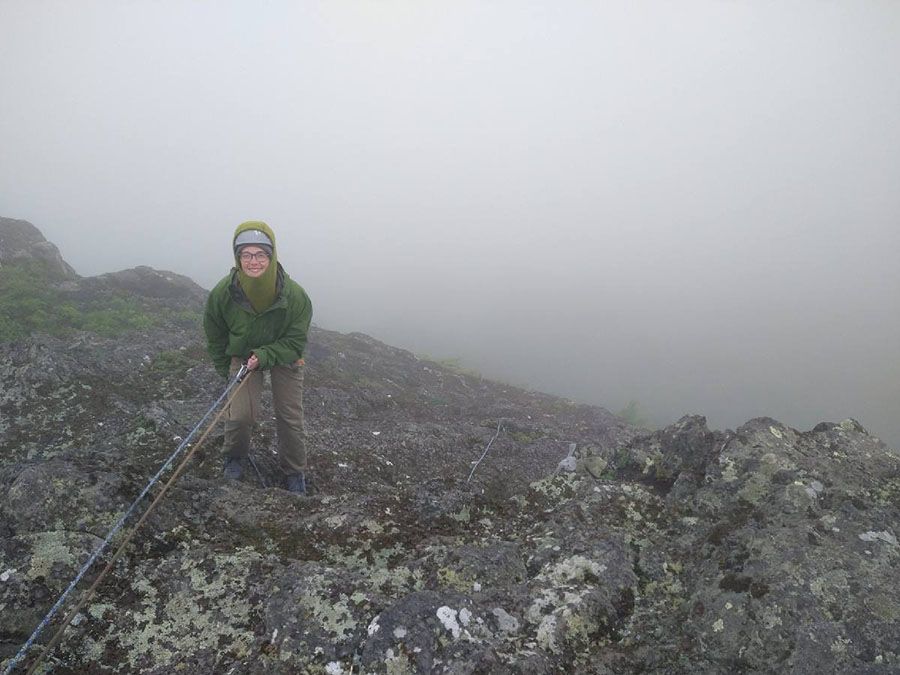

Dr. Matt Estep, a plant geneticist and associate professor in Appalachian State University’s Department of Biology, performs fieldwork at Rich Mountain Bald — part of the Tater Hill Preserve located in northern Watauga County. The preserve is a plant conservation project owned and managed by the North Carolina Department of Agriculture’s Plant Conservation Program. Photo by Ellen Gwin Burnette